Till a few months ago I knew nothing about Maria Prîmacenko (Prymachenko, in English spelling - with an accent on the "e"). At some point, one Facebook post brought her to my attention. I looked her up online, she's everywhere. She is the kind of artist that inspires viewers to feel they stumbled upon essential, primordial, eternal images. I was astounded to discover her.

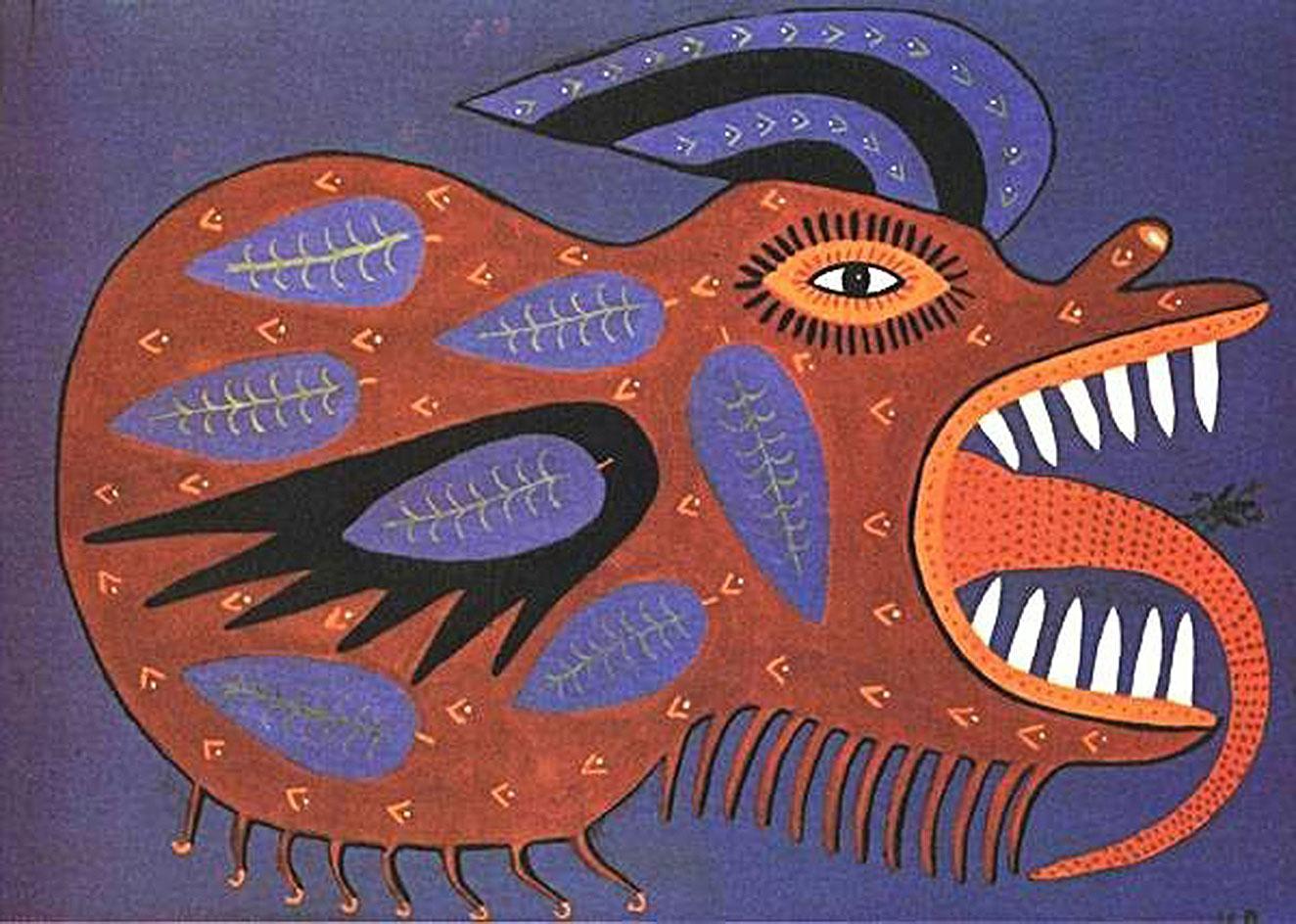

First of all, the colours: always rich and pure, often vivid, in perfectly balanced harmonies. And then the lines and shapes: clear, smooth, deceptively simple and yet, as you look deeper, strikingly sophisticated, baroque. Last but not least, the composition: subjects' centricity, symmetries, a sense of density without feeling ponderous; instead, it's something you can grasp at a single glance, revealing itself in many unexpected subtle details.

And the stories: mundane rural scenes, ornamental flower patterns, birds and other symbols derived from rustic lifestyle (Maria Prymachenko started her career in embroidery, and has always sewn her own clothes), symbolic scenes ( featuring Taras Shevchenko, for example, or scenes of war and peace) and, perhaps the most famous and powerful, the fantastic creatures. I do call them "beasts", and someone has indeed named them, in an innuendo with obvious flair, the fantastic beasts of Maria Prymachenko.

Spooky oddities and other flows

In fact, the Ukrainian artist is creating an entire mythological realm. Although rooted deep in Ukrainian folk art, everyday life around her or Zeitgeist, this universe is profoundly personal and unique. She blends inside of it a solar vitality, a primordial link to people, nature and life itself, mixed in a fantastic, nearly terrifying, paganism. Have you read Gogol, Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka? Or his famous short story Viy, part of the Mirgorod short story collection? These are texts that explore essential flows in Ukrainian folklore - both superficial and deep: wittiness, diligence, exuberance and the bizarre spookiness.

Or perhaps the painter herself was a "fantastic beast". The more I study her drawings (drawn on paper/cardboard, initially in watercolours, later in gouache), the more I read about her, the more I am compelled by this conclusion. A multifaceted talent, by no means ordinary, regardless how much this inner radiance may seem to contradict the stereotypical notion of "peasantry". Her daughter-in-law, Katerina Prymachenko, a fellow villager, mentioned in an interview that people used the fierce temper of her future mother-in-law to terrify her just before the wedding. "Sometimes she would burst through the gates," she said about Maria, "and she'd yell so loud in the street that everyone would flee for the hills."

Art on piglets

Maria Oksentiivna Prymachenko was born in 1909 (on 30 December 1908, according to the old calendar) and lived most of her life in Bolotnea, about 70 kilometres outside Kyiv. The village was a typical Ukrainian settlement, barely over a hundred residents back then. Although the population later increased, it never exceeded four hundred.

She was born in a family of “artists”: her father was a carpenter, specialised in building fences, that he often engraved with depictions of stylized plants and animals, her mother a seamstress (who introduced her to sewing and embroidery), and one of her grandmothers painted Easter eggs.

At the age of seven, Maria caught polio and was only able to complete four grades. The illness left her with terrible pain and a shortened, almost non-functioning leg, for the rest of her life.

I can only imagine what it must have been like for a farm child not to be able to go out to play, not to be able to go to school, not to be able to simply walk, except grumpily, with great difficulty... Being off farm labour allowed Maria more time for herself and I suspect this helped spark her imagination - though not necessarily in bright colours.

So what options would a child without much education have, a child who probably had no friends and spent most of her time alone? She would herd the geese - in fact, that's how she says she discovered the blue clay she first used to decorate the white walls of her parents' house, when she was 17. Previously she only drew in the sand using a stick. From here, the stories branch out. A neighbour boy, they say, saw the flowers in Maria's house and never wanted to leave. His parents came to ask her to paint their house. Another version says that Maria was asked to decorate the house or the stove of some newlyweds and, for payment, received a sow that gave birth to eight piglets and helped the family survive the Holodomor of 1932-1933.

Before drawing, Maria learned sewing and embroidery. This must have been a demanding and time-consuming exercise. In the late 1920s, she was member of an embroidery cooperative in the nearby town of Ivankiv. During a folk fair where the cooperative was exhibiting the crafts of its members, Maria's work was noticed by another artisan, Tatiana Flora, who travelled from Kyiv scouting for local talent. Tatiana came to visit her at Bolotnea, where she was impressed by the paintings on the walls of the house and Maria's album, a coarse sketchbook. She invited her to Kyiv.

On a side note, in the 1920s, the Soviet Union promoted so-called korenisation, encouraging blending of local languages and cultures of the constituent republics, mainly to build loyalty of the masses to the Soviet regime. A large number of Ukrainian-language schools were opened, the party and state apparatus and the management of enterprises attracted local cadres, and a host of Ukrainian-language magazines, newspapers, books and textbooks appeared. Naturally, local folk art was also promoted. Although in the 1930s the process of Ukrainianisation slowed down and then stopped, in 1934 the Art Museum in Kyiv hosted experimental workshops for artisans.

To Kyiv and back

In 1935 Maria joined these workshops and resided until 1940. At some point, the workshops turned into a school for artisans, operating within the famous Kievo-Pecerskaya Lavre. In Kyiv, the young artist is undergoing two medical interventions that have finally enabled her to stand on her own two feet, but she walked on a cane or crutches for the rest of her life and had to wear a heavy prosthesis.

She begins to paint on quality cardboard, large format, using aquarelle, and her colours gradually become more vivid. She also delves into ceramics, moulding painted plates, mugs and the creatures we know from her drawings, but this phase ends soon. The Museum of Decorative Folk Art in Kyiv only preserves a handful of her ceramics. At the time, the museum bought more than 200 of her works, a number of them - the "beasts" - were displayed at the Ukrainian national exhibition, then in Moscow and, in 1937, in Paris.

It is rumoured that, in Paris, Picasso and Chagal were amazed by Maria's drawings. Chagal was so impressed that he allegedly began copying her phantasmagorical creatures. She was sent a gold medal, but it was lost while in transit. More exhibitions followed, in Prague, Warsaw, Montreal and Sofia.

Her fellow villagers were not nearly as impressed. As Katerina, her daughter-in-law recalls: "Nobody paid much attention to these things. But in the 1940s, when Maria brought a gramophone and an iron bed to the village, that's when she became a sensation. Nobody ever seen anything like those, so the whole village would come to listen to the music and have a look at the bed. Maria also brought real dolls to her granddaughters, and all of us girls in the village envied them."

The artist returned to her village in 1940, although she had the option of living in the capital. She never desired to live anywhere else but in Bolotnea. However, it was here that a new series of tragic events happened in her life.

Nazis, a good daughter-in-law and two grandchildren

While in Kiev, she met Vasil Marinchuk, a soldier from Ivankiv, who was visiting the monastery, and they got married. But he was drafted for the Finnish War and left for Finland. In 1941, in Bolotnea, Maria gave birth to her and Vasil's son, Fedir. She wrote to her husband and received a joyful letter in reply. But it was his last, as Vasil was killed in the war. Maria never knew where he was buried and she waited a long time for his return, without remarrying, hoping for a miracle. In her later work, the theme of war and soldiers' graves became central. She was left to raise her child alone, she herself an invalid, with two elderly parents, in an old and crumbling house. Furthermore, not long after the war began, her brother was shot by the Germans. Maria took a job at the Colhoz and stopped painting. She withstood the German occupation until 1944.

Considering she resumed her artistic activity only at the end of the 1940s, there is no doubt that the fifth decade was a profoundly felt tragedy for her. Katerina recalls that her mother-in-law often drew while praying and cursing. Moreover, Maria was a very good fortune-teller. Women in her village used to come and consult her during the war, wondering if they would ever see their husbands deployed to the battlefront. We can hardly imagine how this woman was only able to enjoy a few years of happy young life and how she managed to live through her sufferings, after a mutilated childhood.

In the late 1940s Maria began sewing wedding dresses for the nearby villages. She gradually brightens up and starts painting again: the late 1950s and the first half of the 1960s are practically the most fertile period of her life. She is still in the prime of her life, she is powerful, she is once again appreciated at home and abroad, she becomes an almost canonical figure of Ukrainian folk art, even though Soviet propaganda considers her a representative of "sunny Ukraine", blurring the dark elements of her artistic vision.

She was able to paint using both hands, without any noticeable difference at all. Altogether, it's a tranquil time in the artist's life, a time when her inner strength is channelled into her work. Previously focusing on fairy-tale, fantastical plant and animal elements, she began painting more bright mundane and symbolic subjects. Fedir, her friend and apprentice, gave her a good daughter-in-law and two grandchildren.

Paradjanov's Citrus

In the 1970s, another side of Maria Prymachenko's creativity blossomed, as she began to label her paintings with titles, written on the back with her peasant hand, barely literate. These titles are integral to her works, often long, aphoristic or versified, always in the vernacular, sometimes explanatory, sometimes mysterious: "Nuclear war be damned!", "A three-year-old Ukrainian bull is wandering through the woods to gain strength", "The beast drinks poison, the snake stings him", "Horse with corn in space" etc.

Despite her fame and all the celebrities who would visit Maria, she lived a simple and modest life in her farmhouse, raising pigs, chickens, geese and a horse. Together with her son, she built a new house in her parents' backyard over the course of several years, painting the walls only in the traditional white and the doors in her favourite colour, green. She never sold her paintings, but she did give away many of them.

One of those who would often visit her was the Armenian-born filmmaker Sergei Paradjanov (1924-1990), adopted son of Ukraine and author of the famous film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1965), produced by Dovjenko Studios. Story goes that in a time of scarcity, Paradjanov sent her a box of oranges, something Maria had never seen before. Fascinated by their shape and colour, she refused to eat any, but simply kept on admiring them.

Before the Chernobyl disaster, the painter had a premonitory dream, similar to the one she had just before her husband's death. Although Bolotnea was within the 30-kilometre radius that was immediately evacuated after the explosion, she refused to leave. She set up a decorative writing workshop for children in the village and lived out her old age in peace, painting until her last breath, even though for the last eight years she could not leave her bed. She died in 1997.

Howitzers and 125 buses

I personally dislike sanctifying artists, as it ruins the emotion one receives from their work. Discovering Maria Prymachenko, I tried to get a sense of her world and life. I am now convinced that she was, in a way, an ordinary peasant, tenacious, stubborn, full of superstitions, perhaps sometimes sly or sullen. Her sensibility was shaped under the influence of artistic threads in her family, folklore and the rural and natural environment, but in rather harsh, even tragic circumstances. I suspect it was probably her loneliness that made her preserve deep in her soul something of the joy, the amazement, as well as the fear of a child facing the world - both seen and unseen.

She was undoubtedly an extraordinary native talent and, like all great artists, a brilliant lightning bolt that transforms the electric charge of the surrounding atmosphere into a fascinating drawing in the sky. I hope one day I'll get to actually see her paintings in Kyiv.

Russian forces burn #museum with paintings of Maria Prymachenko.

— Shah Basit (@journoShahBasit) February 28, 2022

A history museum in Ivankiv town, Kyiv Oblast, was destroyed by a Russian attack, according to Ustyna Stefanchuk, an art collector. The museum had about 25 works by famous Ukrainian artist Prymachenkoю pic.twitter.com/sVJD8Eru6h

In February 2022, the Russians deliberately bombed the museum in the small town of Ivankiv, where several dozen of Maria's paintings were preserved. Several were saved by locals who rushed into the burning building. One of them was later auctioned for a record $500,000. Was bought by a Ukrainian from the diaspora, who entrusted it to the Museum of Folk Art in Kyiv, currently housing over 500 of Maria Prymachenko's works. All the money went to the Ukrainian army, a donation that enabled them to buy 125 buses for their soldiers.