Children talk a lot, with high voices, as high as their hearts. But they also speak in different other ways. They speak with their eyes, with quick or shy gestures, they speak through the games they invent, they speak through drawings. Often, if you know how to listen, children also speak through the way they keep quiet.

All around you can hear words in Ukrainian, Russian - quite common in the Odessa region, English and Romanian. I smile at a little girl sitting at a kindergarten table with other kindergarteners, and she confidently holds up her fist in the air for us to bump it in a greeting. On one wall, in front of a snail-like box with a shell full of letters, a little blond boy spells out the Latin alphabet with a Slavic accent. A for airplane. B for bug. C for camel. D for dolphin, E for elephant...

We are at the educational centre opened in an office building in Bucharest by the General Directorate of Social Assistance of Bucharest, Anaid Association and UNICEF. Here, more than 120 Ukrainian children, aged between 3 and 12, are under the care of educators and teachers while their mothers, who they fled the war with, are at work.

The kindergarteners, first and second grade children, prepare their lessons with Ukrainian teachers, two of whom also speak Romanian. It's a kind of homeschooling system, as the teaching staff here help the children to learn the Ukrainian curriculum at a distance. In addition, they study Romanian and English and have workshops where they learn to make small objects or ornaments.

From 3rd grade up, the children participate in online lessons with their hometown teachers. With headphones on their ears and a tablet in front of them, from the same classroom, they listen to the explanations coming to this corner of Bucharest from Kiev, Odessa, Kharkov, Nicolaev or Zaporozhye. They are here, no doubt, but also there.

On Katia's desk - a tall, dark-haired 12-year-old girl - is a sheet of paper on which she drew the right half of a monkey, accurately and daintily. I asked her why she only drew half. "Because my friend sitting next to me will draw the other one," she replied, describing a play of presence and connection in a time of uprooting.

The little boy who draws tanks and battleships

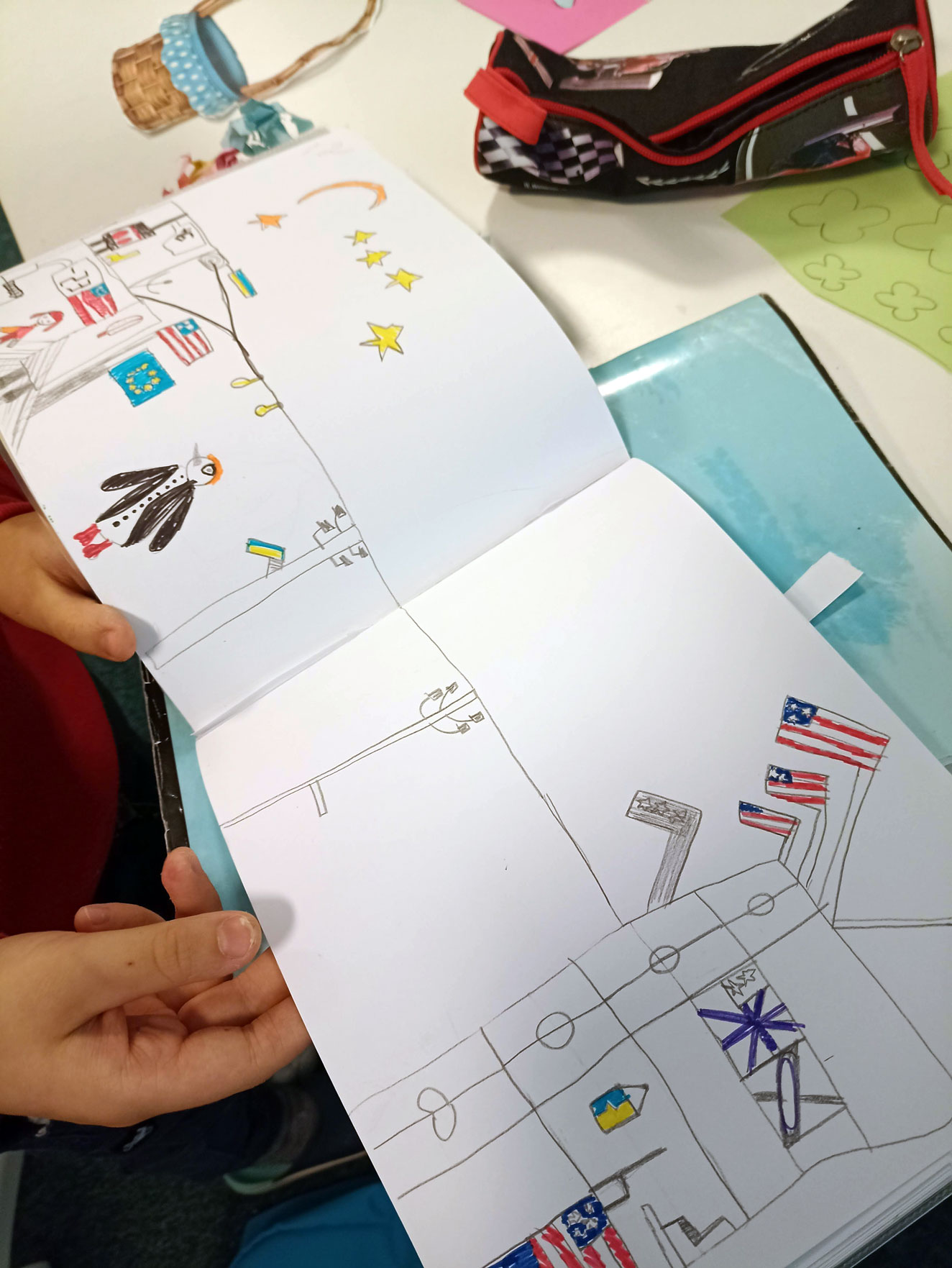

Many of the children here draw. Whatever the curriculum of the day, they have sheets or sketchbooks with pictures on their table or in their schoolbags, referring to a reality rarely put into words: the war. In first grade, Anastasia, a little girl with bright brown eyes and a wide smile, plays translator and explains to a classmate with dimples in her cheeks why we are there.

Born in Odessa, she has a good understanding of Romanian, a language her family speaks at home. From her backpack, she pulls out a drawing of a cat - its face and eyes are painted in the colours of the Ukrainian flag. "In every drawing she makes, she puts the Ukrainian flag," Marina Cojuhar, a teacher at the educational centre who lived in the Izmail region before fleeing to Romania, explains to me in Romanian. Anastasia hears what we're talking about, smiles and shows us other examples of flags in the manual on the bench.

In the second grade classroom, we meet Sasha, who is seven years old and loves to draw. His sketchbook is full: a polar station with American flags and EU stars in the sky, a building with the EU flag, a ship under the Polish flag, a tank with the US flag, a helicopter, rooms in military buildings with maps and charts on the walls, people with guns. But he doesn't like to talk about the images he puts down on paper - he just shares his creations, row by row, and they speak for him.

In middle school, Katia and Karina want to chat in English, to practice their conversational skills. Karina is in the third grade, she is from Kiev and has a younger sister for whom she has just made a rainbow-coloured postcard. Katia, the 12-year-old who used to play half-draw with her classmate, has a naughty five-year-old brother who, she claims, runs around all day. When they get home in the evening, the girl watches cartoons, draws and talks to her friends back in Ukraine about what they've been up to. Never about the war.

But the reality of war is always there and makes its presence felt when you least expect it. Roxana Iacob works at the Anaid Association and runs creative workshops with children. Because she always brings along little crafts, some of the children call her Roxana Bouski, Roxana Mărgeluțe. She recounts a time when several artists came to the centre and played drums. Hearing them, a little boy started screaming and crying in horror: the loud noises reminded him of bombings. Another child was always sad and frequently cried when he came to the centre. Schoolteachers later found out that she had watched from the window of her apartment as the school she went to every day was blown off the face of the earth by a missile. "I always receive drawings from the children, and one day a five-year-old girl brought me a drawing of dead people. I got worried and told the psychologist Cristian Andrei, who is constantly dropping by. He explained to me that drawing is the way children so young express what they experience," says Roxana Iacob.

„'Mom, the rocket! It chased us all the way here!”

Marina Cojuhari is Ukrainian and learned Romanian as a child, in her village, where everyone spoke it. At home, she was an English teacher, and today she works as an educator at the educational centre in Pipera. She fled to Romania with her three children and her husband and found a home near Otopeni airport.

"When we got there, a plane was preparing to land, and the my boy said to me, 'Mom, the rocket! It chased us all the way here!" she recalls. Her colleague, Alla Munteanu, was a teacher in a village in Izmail for more than two decades. When she was home, her job was much simpler than it is today, when she is teaching refugee children, just like her. "You can immediately feel the difference between a child who has no worries and a child who fled the war. Now we have to carefully prepare for each lesson. If it's something about family, fathers or grandparents, we have to find out about each one of them: Is everything OK at home? Are they all well?" Her colleague, Marina Cojuhar, complements her: "We are careful not to get too close to the heart with what we say. There are heart-strings we strive not to touch."

But there are many roads that lead to memories, fears or sadness, and you don't know when a sound, an image, a word or a smell is going to lead you down one of them. It's springtime in Bucharest and the streets are full of people selling flowers and people holding bouquets. "Everywhere smells of hyacinths and it reminds me of home. I had a garden full of hyacinths," says Marina Cojuhar.