We consider humanity to be evolved, educated, and compassionate… Then all of a sudden new deportations, executions, and massacres take place. Yet, when dust settles and screams subside, it is common for politicians, philosophers, writers, and journalists to express their outrage and disbelief, wondering how could such atrocities and barbaric acts recur… in the 20th… and 21st centuries. The Armenian genocide, the Holodomor, the Holocaust, the destruction of the 1,800-year-old Buddha statues in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, the Rwandan genocide, and the destruction of 28 ancient monuments in the 3,500-year-old city of Palmyra are but a few examples of the brutal reality.

For years, I too had believed in the triumph of peace, democracy, and prosperity over war, authoritarianism, and poverty. But on February 24, 2022, as Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, that belief was shattered. Soon, reports emerged of civilians being killed, beaten, robbed, and looted. I wondered that, perhaps, we are not doing enough to protect potential victims; that we don't reveal the roots of evil to prevent such terrible things from happening again. These horrors are a harsh reminder that "The End of History'' declared by Francis Fukuyama did not happen in 1992. Then there are also the words of philosopher Hannah Arendt who, in the second half of the 20-th century, said, “It is true, for the first time in history all people on earth have a common present: no event of any importance in the history of one country can remain a marginal accident in the history of any other.”

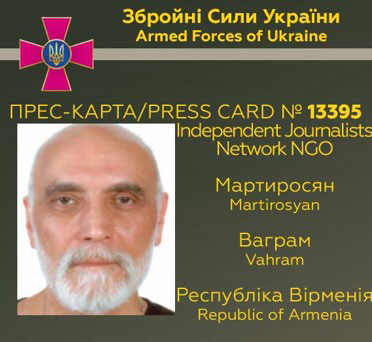

So, I decided to go to Ukraine, witness the war. I couldn’t help but wonder: is it enough to simply bear witness in times of war? Apparently, no Armenian TV station had sent journalists to cover the war. The Armenian media landscape is heavily influenced by local agents of Russia and the propaganda, manipulations, and disinformation spread by the three Russian channels that are freely broadcast in Armenia. These channels are able to operate in Armenia due to interstate deals, which were not terminated despite the new post-revolutionary Armenian government coming to power in 2018. I felt compelled to take matters into my own hands and shed light on the truth. I decided to report on the conflict firsthand, although it had been some time since I had worked as a reporter or presenter.

It is Not Easy to Even Get to Ukraine

Finding a producer who shared my vision was the first challenge, but I was ultimately successful. During one of my meetings, I was told about Gars Khachatryan, the author of the 'Usual Denazification' project, which aims to present the war against Ukraine to the Armenian public. He organized the entire trip.

However, when it came to hiring a cameraman, we encountered a new hurdle: most were either too cautious, or demanded exorbitant fees. In the end, we found a photographer with some experience as a cameraman, and set a departure date. But then it proved difficult to actually make it to Ukraine - our journey was postponed several times due to various obstacles and challenges.

Traveling from Armenia to Ukraine has become increasingly challenging due to limited flight options and visa complications. Last year, Ukraine, with a population of more than 40 million people, had only two main airports working… This lead to overcrowded airports and frequent delays in Chisinau (Moldova) and and Warsaw (Poland). The recently introduced Yerevan-Chisinau flight has had its share of unpleasant events, including cancellations and delays. Additionally, obtaining a Schengen visa for travelling to Warsaw has become a major issue, because of high demand from Armenian travelers wishing to visit EU countries or the Schengen zone, particularly in the aftermath of our 44-day war in 2020. This led to a backlog of visa applications at consulates, which has increased significantly in recent months.

As I navigated the visa process, I couldn't help but notice the long waiting times for appointments on the consulate's website, which could take weeks or even months to obtain. Even though the Polish Embassy provided swift support in obtaining the visa, still we faced a delay, as we also needed accreditation from the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine.

When we finally secured all the necessary permits, we were met with another hurdle: the flights to Warsaw were fully booked. Frustrated by the perspective of further delays, we opted to fly to Warsaw via Tbilisi (Georgia).

Ukraine Begins in Poland

Upon landing in Warsaw we hailed a taxi to take us to the bus station. The driver, to our surprise, was a Ukrainian woman named Yulia, a history teacher who had emigrated to Poland. I've learned from experience that it's best to act promptly whenever possible, whether it's asking someone out on a date, buying a new outfit, or conducting an interview. So, I asked Yulia if she would be willing to share her story as long as it didn't interfere with her work. She agreed.

As we drove through the quiet streets of Warsaw, we were struck by the absence of traffic on the wide avenues of the city. Yulia warned that she might say things that not everyone would find acceptable, but she preferred to be honest. I asked her to share her thoughts.

Yulia had left her home in Krivoy Rog, Ukraine, to escape the ravages of war. She recounted how she woke up to the sound of an explosion on February 24, 2022. Her boss called and declared a state of emergency, advising her not to go to work. Yulia took this as a sign to leave the city with her children, quit her job, and left everything behind to seek safety in Poland.

"I quit my job in one day, probably because of my female intuition," Yulia explained. She had taken her children's documents from school, handed over the apartment they had been renting, collected their essential belongings and, on February 25th, 2022, left home for Poland. Despite the traffic jams everywhere, they managed to cross the border on February 27th.

"And how did you decide so quickly to follow your intuition?" I asked.

"How? The city is near the Russian border and at risk to be occupied; don't you know about the atrocities of the Russian army?" Yulia replied irritably.

Her decision to leave everything behind and flee to Poland turned out to be a wise one.

- Before February 24th, 2022, when the war began, the population of Krivoy Rog, was more than 600,000. A few months later, on December 16th, 2022, rockets damaged 43 buildings, 3 schools, and 1 medical facility. And on January 14th, 2023, another 50 buildings were destroyed, resulting in many victims and wounded. Over 100,000 residents fled the city because of the violence, but 75,000 people moved in from other parts of Ukraine, where it was even more difficult to live. Although the Russian army had been pushed away from the outskirts of the city, the shelling continued.

I asked Yulia about her family. She told me her brother and his wife were still in Krivoy Rog because her brother was under 45 and unable to leave Ukraine, and his wife didn't want to leave him alone. Her parents also refused to leave their home in the nearby village because of their age, although Yulia believed they were not really that old. She lost contact with them for two weeks in March 2022 when the Russians occupied their village, took away their phones, and damaged the cell phone tower in Krivoy Rog.

"What were we thinking about when we had no access to information? We were trying to find it. Somewhere, someone saw something, someone else heard something. In short, thanks to word of mouth, one day we heard that my family was alive and still enduring. Then, when we got in touch again, I realized how difficult their life was. They had all changed a lot, both on the inside and the outside,” she said.

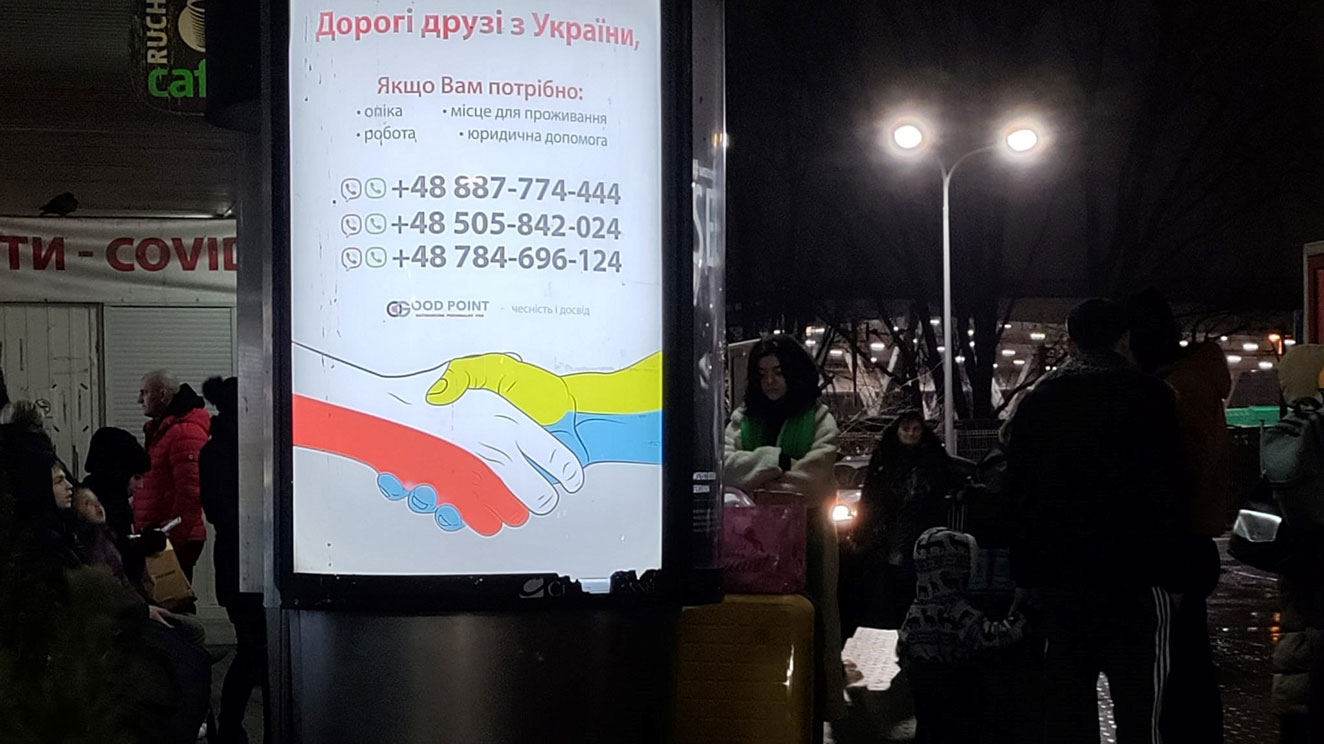

- In the first nine months of the war, 7.6 million Ukrainians entered Poland, with 1.5 million of them receiving refugee status.

“Did you settle in easily?” I asked.

"We all got sick during the first weeks," she said. "My children, Matvey is 8 and Maxim is 12 years old. We were cold and hungry on the way. We were restless. When we arrived in Poland, we rented a room in a hostel outside of Warsaw. I didn't ask for help from volunteers. I don't know why. It didn't work out. But the hostel owner and his wife helped us a lot. I'm very grateful to them. They didn't give us money, but they provided us with information that helped me get my first job here at a "Banquet Hall." I had to clean up. If weddings or birthday celebrations took place during the night shift, I had to wash the dishes too. It's called "pshentanie." Then I sorted packages and parcels in a place like a post office. It was not an easy task either. Different parcels were arriving; some of them were my height and weight. I worked for two months. Finally, I ended up in this taxi, thanks to the advice of good people. So far, I like this job the most."

She did not follow the news from Ukraine, as she found it too emotionally draining, and instead preferred to focus on her family and her job.

"I hope my compatriots will forgive me, but I'll be honest - following the news from Ukraine is just too much for me, emotionally. I prefer to concentrate on my job and taking care of my children," added Yulia.

She shared her last name, "Should I tell you my last name? It's Polyakova, Yulia Polyakova. Fate brought Polyakova to Poland."

Our film crew then arrived at the bus station in Warsaw.

Bus or Train? Performance or Party?

We had initially planned to take the train, but there were very few trains available, with very short transfer times, and, of course, trains were also considered the most dangerous mode of transportation due to attacks.

- On April 8, 2022, the Russian Tochka-U missile strike on the Kramatorsk station killed 60 people, including 7 children, and injured 100 others.

As we looked around the bus station, we noticed that the majority of passengers were women and children. There were only a few men who were obviously past the conscription age of 45. Dozens of buses were departing, and it was clear that many people were leaving Warsaw to return to Ukraine. I was curious about their stories, but I also felt uncomfortable about invading their privacy, knowing that they had likely gone through nightmares.

Despite my reservations, I decided to overcome my introverted tendencies and try to get to know these ordinary Ukrainians better. Although my gray beard might not have made me an evident choice for the genre of vox populi, I was determined to learn more about Ukraine and its people.

After conducting the vox populi, we boarded the bus. Our destination was Lviv, where I had to meet and interview Ivan Cherednichenko, the conductor of the Lviv National Opera. I have not met anyone in Ukraine whose life was not radically changed by the war that began on February 24, 2022. Many people have lost not just one, but several relatives, their homes, and their cities. Ivan is one of them; his parents were killed by Russian occupants in Irpin, near Kyiv. Lviv is located far from the battlefields, but it was bombed and fired upon with rockets many times.

After enduring a long day of travel, including many hours of waiting at the border, I collapsed into my hotel room and sank into a deep state of exhaustion. It was in this state that I first heard the air raid alert. Summoning all my remaining strength, I crawled to the window, opened it, and turned on the video camera on my phone to capture the sound before collapsing back onto the bed. I needed to recover before filming at the Lviv National Opera. The general director of the theater, Vasil Vovkun, had agreed to let us film the Christmas performance and interview the artists.

We hired two more local professional cameramen and began filming at the theater in the evening. We were told that we were also invited to the corporate party, which was scheduled to take place in the Mirror Hall.

I wanted to gather a group of artists around a table to discuss their personal experiences since February 24, 2022, as well as the cultural aspects - 'innocent' classical music was strongly encouraged by the Soviet regime because it could integrate Ukrainians into the rich traditions of Russian musical arts, connect rather than divide the two nations. I was hoping Ivan Cherednichenko would also participate in this conversation, and I didn't want to focus solely on his personal tragedy.

Unfortunately, we were unexpectedly prohibited from filming the corporate party by the general director when we entered the Mirror Hall to assess the lighting. We were informed that he did not want people to see the artists at the party during a time of war. While the party could still be held, we were not permitted to film it. Thankfully, Ivan Cherednichenko agreed to an exclusive interview the next day. After a much-needed rest, we met on Armenian Street, in the Armenian Cafe, the only cafe in Lviv that was working without electricity thanks to a generator familiar to us Armenians since the early 1990s, during the first Karabakh war.

The word 'Armenian' is frequently used to refer to the Armenian community in Lviv, which has a long history dating back to the Middle Ages. The community is centered around the Armenian Apostolic Gregorian monastery, which was established in 1363. However, during the Soviet period, in 1945, the monastery was closed and the Armenian community was nearly eliminated, and it resumed its functions in 2001.

Don't Shoot the Conductor in the Back

"I was supposed to be in Irpin with my parents on March 8th. I've had a pretty busy few months, including premieres, and Vasily Vovkun gave me a few weeks off. But the guest conductor, whom I invited to conduct my performance, refused... due to the tense situation. On February 23rd, they called me from the theater and asked me to return, and I left for Lviv," Ivan remembered.

He arrived in Lviv at half-past three in the morning and was surprised to see, around midnight, a military column leaving towards Kyiv along one of the sections of the route. He went to bed, and at 5 in the morning, his phone started ringing. His friends from Lviv and Kyiv called him. Initially, he didn't attach much importance to this, but around 6, he noticed too many missed calls and decided to call back the most recent number. It was from the general director who told him that the war had begun. Immediately, he called his parents in Irpin, and his mother confirmed that there were already Russians in Hostomel and that she had heard gunshots.

- Irpin (population - 70,000), Bucha (population - 37,000), and Hostomel (population - 17,000, with a large airport) were among Russia's primary targets. The bodies of hundreds of civilian victims were found there by Ukrainian military forces who liberated these cities.

When Ivan's sister left Irpin, she offered the parents to leave with her. They flatly refused, not without a scandal. She moved to Lviv with her child. Soon after, all roads from the city were cut off, and the Russians already entered Irpin. They cut communications and electricity. For a long time, Ivan could not find out what happened to his parents. His father had difficulty walking and used a walker, so Ivan talked to volunteers who promised to help transport his dad and his mom out of the area.

"On March 17, I was about to go there, not to Irpin, but in the direction of Irpin because I could not get into the city. The volunteer who promised to help us called and said that it was impossible to get there on that day, that full-fledged battles were taking place, artillery shots, and no one was allowed there. We should wait. Then we found out we were waiting pointlessly. On March 25, a neighbor who managed to escape called me and said that my parents had been shot," Ivan recalled.

Ivan and his relatives talked extensively to eyewitnesses. They were told that the Russians had knowledge of the location of people and used an armored personnel carrier to navigate the streets. The Russians fired incendiary cartridges at the houses that had a light inside. Anyone who tried to escape was shot on sight. This happened not only in Irpin but also in Bucha and Gostomel.

"Why didn't your parents leave Irpin? Did they trust the 'rashists'?" I asked.

"No, it's been a long time since we've known who they are in Ukraine. But you know, there are people who are very connected to their inner circle. My mother loved her house very much, and for a long time, they were engaged in fixing it up. It was her sanctuary; she couldn't leave it. And so many others felt the same”, says Ivan. He then tells me what happened to his parents: “The house caught fire. The fire spread to the garage and the other buildings. My parents opened the gate to escape. My father used a walker, so he was slow to get out. He had just stepped out into the street when the soldiers shot him. My mother came out of the house a bit later with some necessary items. She ran towards the soldiers, apparently in a state of shock, and she was also shot. This is the picture we've put together from what eyewitnesses have told us. One eyewitness escaped at night and hid in the woods for two days. An elderly couple, whose club-type house was diagonally across from ours, saw everything from the fifth floor. Then the machine gun was brought up to the fifth floor, and they were fired at. The entire floor and the attic collapsed on them, and they were buried in the debris. They heard the voices of the 'rashists' as they searched for survivors, but they couldn't be found in the rubble. The attackers gave up and left, and the couple remained buried for two days until they were rescued by emergency services," Ivan explained.

Civil Defense Forces were able to retrieve Ivan's parents from the street only on April 4th, as his father's body was booby-trapped. This was followed by a harrowing journey to the morgues, as Ivan's parents had no identification and were labeled as "unknown man" and "unknown woman”. With the morgues overwhelmed by the sheer number of bodies, many lay on the streets, and relatives had to sift through bags to identify their loved ones. It took three days for Ivan to locate his parents. After a police examination, they were finally buried on April 11th in Irpin.

In Irpin, there was no smell of gunpowder, the ruins already seemed old, but no smiling people

There are 446 kilometers from Lviv to Irpin. I traveled there, located Ivan's father's house, and spoke with an eyewitness. With obvious efforts on his part, Alexander Parkhomenko, like many other Ukrainians, agreed to an interview about the tragic events. It's crucial to inform everyone how harsh the reality is.

He lives about "ten houses” away from Ivan's home, but he didn't know much about Ivan's parents. Alexander was sitting on the curb when he saw a woman lying by the tumbled-down fence with a small dog lying on her chest. He burst into tears when he saw it. Alexander then went on to describe how the street dogs had damaged the bodies over a week. Alexander’s godfather, who lived on the same street, had also been killed: two shrapnel wounds. The godfather’s neighbor also died, but Alexander didn’t know how it happened.

I spoke with other residents of the city.

Anatoli Harnik now lives alone. Although his house is not destroyed, there is no heating, and the roof is damaged. Thus the children and grandchildren, whose drawings take up an entire wall, live in different cities in Ukraine and Germany. He showed me the walls that had been hit by bullets. The next house was hit by a shell, and the neighbor died. Like many elderly Ukrainians, Anatoli Harnik asks why they are shooting at civilians, what have they done to deserve this, and how is it possible?

Galina began her story with the World War 2 German occupation. In 1941, her mother Nadia was taken to a concentration camp in Germany, where she was subjected to beatings with whips and left hungry until a German family took her into their home. Fourteen years later, in 1955, Galina was born in Ivankovo. Her mother died soon after childbirth. Two weeks after her birth, Galina was taken to Irpin where she lived for the past 68 years, without traveling anywhere. She felt the first explosion at 4 o'clock in the morning and believes that the attacks began from Belarus.

"When you were occupied, how did you feel? Were there any face-to-face meetings with Russians?" I asked her.

"The 'katsaps', the Russians, came to my apartment. I heard the dogs barking. Six people with machine guns knocked on my door. I opened the door and they pointed their guns at me. They were young guys with a Moscow accent. I had a friend who came to visit me from Moscow, so I could distinguish this accent. But they didn't kill me. 'Where are the soldiers?' they asked. I said there weren't any. They said, 'Who's home?' I said, 'Three babushkas and two dedushkas.' I wanted to say three girls and two boys, but I thought the girls would not be left alive; they would be killed. They left us... My God, I used to love the Russian language because it is so easy and melodic, and Ukrainian was difficult for me. But now I hate Russian; I hate every word of it. Do you understand?"

I understood her, of course. I just didn't agree with her that Russian is more melodic than Ukrainian, even though I only know Russian and not Ukrainian.

The Black and The White

At the Christmas concert, Ivan smiled and played pranks with an umbrella, following the script. I wondered: were they not afraid of being accused of putting on such a lighthearted performance during such a terrible time?

"It caused a debate in the theater. But after weighing all the pros and cons it was decided to launch this project, because a theater’s role is not only to reflect the current events."

Every initiative is commendable if it helps people cope with difficulties. Ivan's idea, especially considering the strong Viennese tradition in Lviv, was to transport the audience somewhere else, far from the war, to the ambiance of old Viennese balls.

"Now Ukrainian society is divided into those who defend Ukraine and those who help defend Ukraine," Ivan said. "And it cannot be otherwise; there can only be black and white. We have a war here."

The black-and-white style has a strong impact on photography and film. In the case of the black-and-white war, even if you are a journalist who should be unbiased, you don’t think about the aesthetics of the lack of colors; you also choose a side.

***

About the author: Vahram Martirosyan is a prominent Armenian writer, journalist, media researcher, and translator. He is widely recognised for his translations into Armenian, of Hungarian and French literary works.

Translated by Vahe Ohanyan