We resume with the second and final part of yesterday's analysis of Russia's efforts to influence politicians, journalists, opinion leaders and, ultimately, public opinion, through disinformation campaigns designed for European Union countries by mischievous Kremlin strategists.

Italy: an investigation leading to an unclear outcome (so far)

In this whole story of dealing with Russia, recent years Italy is a textbook case. Beyond Berlusconi's personal friendship with Putin, Russia has been an area of great economic interest for Italian business since 1989, making the sanctions that followed the invasion of Crimea and, more recently, those following 24 February 2022 a major headache for export and tourism companies. Since before 1989 there has been a certain cultural sympathy for everything happening in Moscow, and Italy's foreign policy has also been very open to Putin's Russia. But the war broke up this marriage, under both Draghi and Meloni administrations, both of which sided unreservedly with Kiev. In fact, military support was voted by all the political parties represented in the Italian parliament, even if some of them subsequently went around the corner, in a perfect demagogic style.

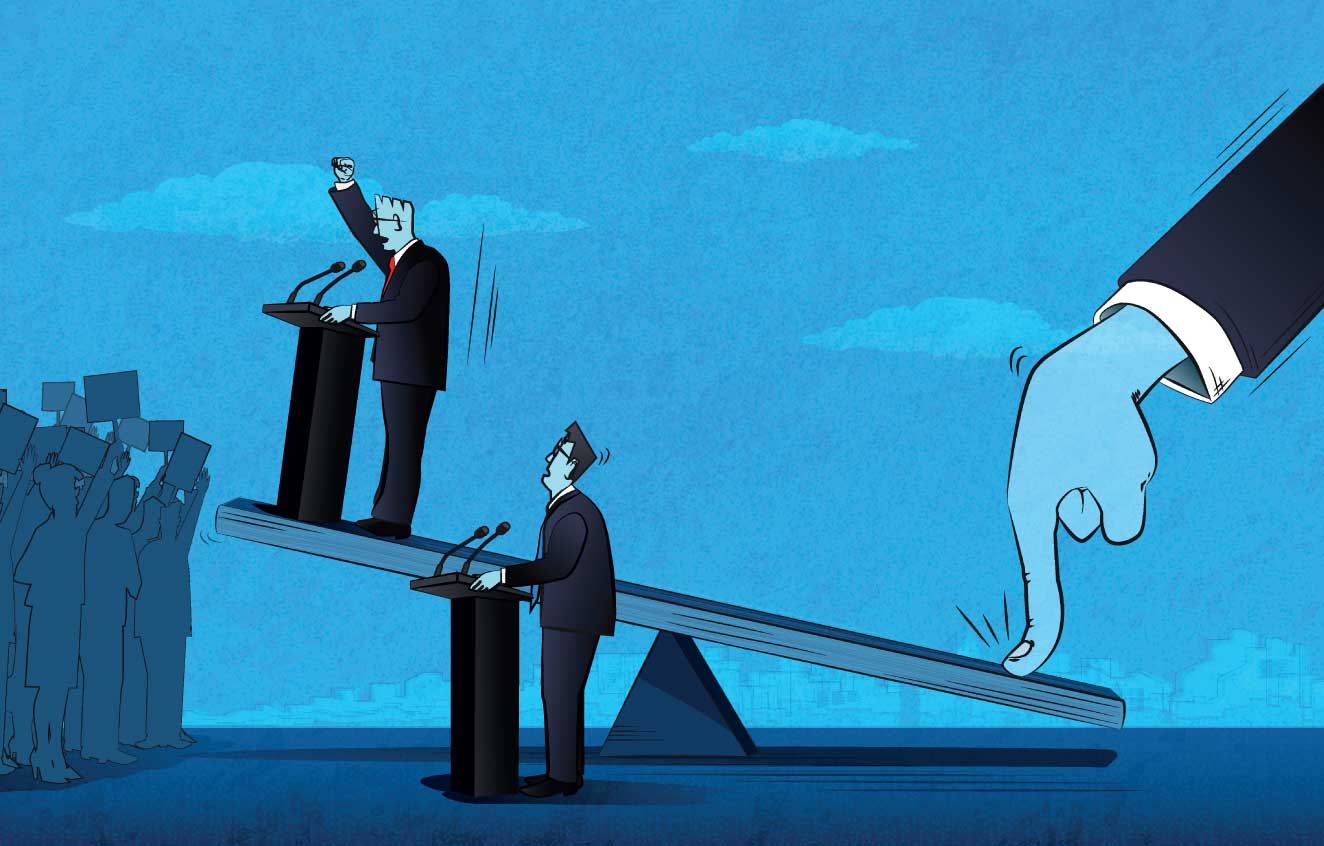

However, the government's position did not coincide with that of the Italian media. At the beginning of the war, the frequency of messages inspired by Russian propaganda was huge on the major TV channels, to the point where RAI management had to intervene in the selection of guests for the shows. In the meantime, however, very few voices against supporting Ukraine remained in the major media outlets, and the same happened on the political scene. A background note: Italy was the only country in the European Union where a TV channel (part of the Mediaset group, owned by Silvio Berlusconi and his family) did a live interview with Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov.

It is still unclear how many of these voices embraced Kremlin propaganda out of conviction and how many of them out of interest. Last autumn, the parliamentary intelligence oversight committee Copasir announced an investigation into possible funding from Moscow, after The Washington Post wrote about a list of 14 countries where money from Russia poured in for propaganda. There is no public report from the commission yet, but Corriere della Sera reported that it received a list of about 20 people who are rolling out Kremlin messages on TV and especially online. They are rather lone wolves, and with a few exceptions, virtually unknown names to public opinion on the peninsula.

UK: BBC tackles fake news

No official information from inquiries into Russian propaganda is available to the British either. Theresa May called for an investigation into the matter, but it all went into limbo. The current British administration is mainly dealing with the not-so-simple post-Brexit economic consequences. Meanwhile, the penetration of Russian capital into the UK, especially in London, is widely known, so the Russian issue remains a sensitive one for the public. Similar to Italy, however, the British government has been a strong supporter of the Ukrainian cause, including the Boris Johnson cabinet.

The UK government runs an agency tasked with reporting and eliminating as much fake news and shady accounts spreading it as possible, but there is no official data on the outcome of its operations. Russian influence in shaping British public opinion in the context of the Brexit campaign is also notorious.

In the last few years BBC developed an important tool to expose fake news, which, in addition to dealing with fake news, also covers Russian propaganda. The British public service discovered that Kremlin propaganda is penetrating Arabic-speaking countries via one UK-based media company. Other regions are also targeted. For example, Sputnik is heavily focusing on Spanish-speaking communities in South America.

Analysts argue that Kremlin's goal is to win over public opinion in poor countries around the world, already largely controlled economically by China, and where "American imperialism" is under constant attack. The Russians hope this will gradually isolate the Western world from the rest of the planet. Hope or illusion, we shall see.

Romania and Hungary, a black & white story

In Romania, where politics become more and more opaque, serious debates about the extent of Russian propaganda are almost non-existent. Little is known, who, how and what comes from Moscow, and how much is toadyism, in the present days or in the past years. At first glance it seems propaganda lost ground over the past years. But lacking official data, one can only observe and assume.

Quite the opposite applies to Hungary. A comparative analysis of the two countries places them very much in opposition to each other, Hungary being Putin's megaphone in the EU. Anyone who had the pleasure of watching the news on Hungarian state television stations, and even private ones, could easily recognise the familiar mix of anti-war propaganda messages and be thrilled by the abundance of fake news. The way the Hungarian TV is painting the war takes you back to the Ceausescu era. Only the decor, the clothes and probably the perfumes have significantly changed.

Bulgaria, €2000 monthly

Bulgaria's record is not much better either, with little information on the subject. But the Russian influence is palpable and visible. A Bulgarian official declared anonymously that journalists, political analysts and other influential personalities received €2,000 a month for publishing pro-Russian content on social networks and in the media. Fake accounts, bots, trolls - basically every weapon in the arsenal of disinformation - have also been uncovered.

Prague spring and propaganda

This year's Prague spring had other significance. One of the candidates in the presidential elections was the populist former premier Andrej Babiš. He built his campaign around the fear of war, arguing that his opponent, a former military commander with high NATO command, would push the country into war. In the end, Petr Pavel (pictured) barely won the battle, unfortunately for the Kremlin. But the reality is that the president has an almost decorative role in the Czech Republic, as the country is a parliamentary republic.

Slovakia: the autumn bet

Next door, in Slovakia, a routine military exercise was used by a disinformation website to create panic over government's alleged intention to declare general mobilisation in the context of the war in Ukraine.

Propaganda is sharpening its claws because early parliamentary elections are due in autumn. Slovakia is of particular interest for the Russian propaganda because the current government announced major military aid for Ukraine. The government is only instated now, but no longer in office because it failed a vote of confidence in parliament precisely because of its pro-Atlantic orientation, amid a major pro-Russian opposition, which repeatedly claims that sending weapons to Kiev will cause "hundreds of thousands of deaths".

Poland: today tanks, tomorrow children

In Poland, a neighbour of Ukraine and a key ally of Kiev in the war, Russian rhetoric also managed to massively penetrate. On institutional websites, the authorities are taking turns to expose Russian narratives in order to debunk the propaganda and undo its effects: Ukraine is a country with expansionist tendencies, in reality seeks to annex Poland, a country full of homosexuals, a satellite of the Americans, and so on and so forth.

A so-called Polish anti-war movement emerged this year, expanding the Russian narrative. Today they want our tanks, tomorrow they'll ask for our children, chanted, among other slogans, the leaders of a demonstration organised by this group; a rally that ended with the epic Yankees go home! And this is only one of now quite many groups in Poland opposing the so-called "Ukrainisation", with leaders well-known in the past for their controversial political views. Their strength, however, remains marginal.

Similar to Hungary, Poland is also facing international criticism for its excessive control of the media, even though its position is completely opposed to that of Budapest. Different countries, with different issues and different views, still Kremlin's messages flow freely.

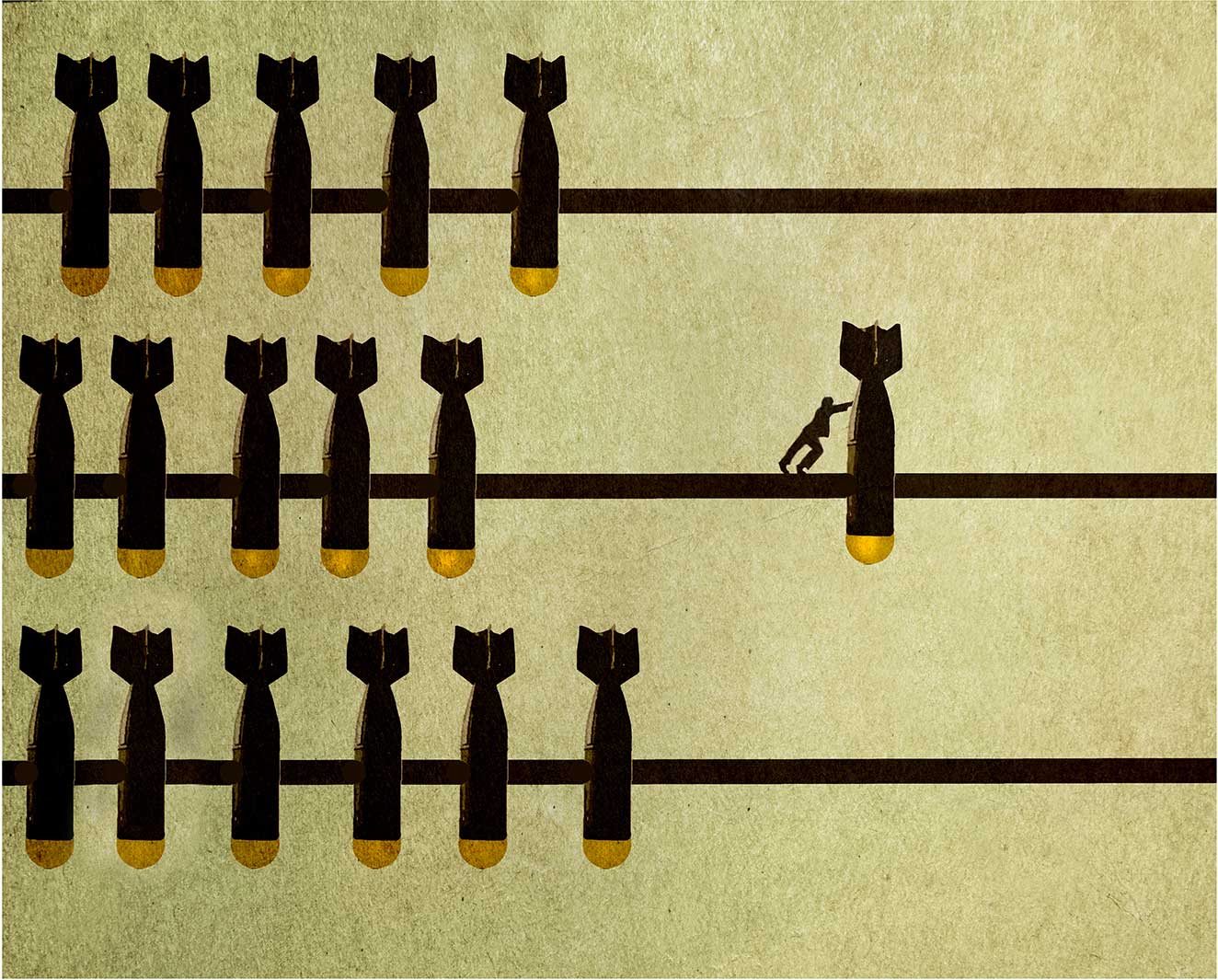

A complex transversal situation, starting to feel like a total information war, while very few can distinguish facts and their objective depiction from the counterfeit ones. "We can refrain from saying it because it's scary, but we are in the middle of a hybrid world war, even if not all of us fight on the battlefield," says Anna Zafesova, Moscow correspondent for La Stampa.

When it comes to the past, there is still the question of whether dezinformacija ever stopped and whether the Cold War ever really ended. Looking forward, another question begs for an answer: what new monsters will be born out of the new artificial intelligence left in the hands of populists in the East and beyond.