Andrei, Maria and their five-year-old son Victor, a young family from Russia, are one of thousands who fled their country after the war with Ukraine erupted. They left everything behind and came to Cluj, where Andrei's father has now lived for several years. Andrei's great-grandfather was born near Turda and died in Russia, after being taken prisoner in the First World War.

It's too warm for mid-January, it almost feels like spring. Ioan Pop waits worryingly in front of the sliding door at International Arrivals. For half an hour they haven't flinched, everyone else has left. Everyone except the people he is waiting for. He prepared sarmale, left them hot, but now they'll get cold.

He shivers when he sees his daughter-in-law coming. She's with a border guard. Worry is obvious on John's face. Polite, but suspicious, the border guard asks him if he knows the girl.

"Sure, she's my daughter-in-law! Her husband is my son. Victor, their son, is my grandson!"

Further answers to additional questions followed: the purpose of the visit, for how long and where will they stay in Romania. Ioan Pop answers them all. Then he boldly says: "Please, they are my children. They came to me. The sarmale are getting cold..."

Thirty minutes later, in front of the sliding doors of the "International Arrivals", out of the airport named after a serf from Cluj, Ioan Pop holds his grandson for the first time ever. So far he only saw him in photos and on WhatsApp.

Maria, Andrei and little Victor are Russian citizens. They fled the country, like hundreds of thousands of others, after Putin announced the mobilisation at the end of September.

They're on the road for three months.

"Do svidaniya, mama!"

On the last Sunday of September, Maria and Andrei were talking uneasily: Putin had announced the partial mobilisation a few days earlier, and Andrei, who had been working from home for the past few days, had heard that the guys at work had been asked to fill out some paperwork. He knew what that meant, he knew it would be his turn on Monday.

"Andrei, if we don't leave today, we'll never leave," Maria told him. He agreed. They took out their luggage and started packing. But where do you start when you have to leave home and don't know when you'll be back? You prioritize. First the kid's clothes, then some toys, the Mickey backpack. Food, water. In the meantime, the external hard drive was copying documents, photos. Andrei packed his cameras (he's passionate about photography), projector, laptop, valuable little things. Good to sell, if needed. In the last moment they thought to also pack their winter jackets.

A few hours later, around ten o'clock at night, the three of them were already in the car. Andrei typed the destination "Yerevan" on his phone screen. That's the way, the coloured line, 15 hours, across the border. He pressed "OK" and put the phone in the holder on the dashboard.

Maria called her mother and asked her to come out to the window as they were going to pass by. "We stopped and we waved from the car... We didn't step out, we'd be heaving too much to talk about... So we just spoke briefly. I said, "Bye, Mom!" and we drove away. We had to get to the border," Maria says. Tears came to her eyes then, and she cries every time she remembers that moment.

Four metres a day

Andrei drove all night. His eyes were burning, but his adrenaline kept him going. There was so many police checkpoints, there was no way he could avoid them all, even if he took the back roads. Somewhere, a patrol had stopped traffic altogether. They'd been stuck there for three long hours.

"We were worried, we thought they were going to turn us around. But they just asked for money," says the young man with disgust.

In the morning they arrived in Vladikavkaz, a town in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains, in North Ossetia. From there it's usually about half an hour to customs.

"When we arrived in Vladikavkaz, the queue of cars trying to cross the border was 20 kilometers long," Andrei recalls. They couldn't believe that so many people were suddenly crossing out of the country. Young people fleeing the mobilisation, families trying to stay together, people whose only form of protest against Putin was to leave.

Andrei, Maria and Victor waited in line for three nights in a row. Andrei had hardly slept at all, set to be on alert in case the queue advanced. At night they were very cold, so good thing they had taken their winter jackets! But Victor hadn't worn his winter coat since last year, and there's a difference of a few centimeters between four and five years old, and his hands were a bit short.

Their greatest frustration was when they realized that another day had passed and they had just made four meters, ten meters, six meters. More and more people were running out of gas, water, food, hygiene items. The hustlers appeared, selling everything at ridiculous prices.

"You weren't allowed to cross the border on foot, but you were allowed to cross by bicycle. Bicycles were rented for 1,500 euros for people trying to cross the border. You'd ride your bicycle into Georgia, drop it off with someone who would take it back to the Russian side, where they'd rent it again, over and over."

There were all sorts of rumours: that the border was going to be closed, that someone had fallen into the ravine, that a child died because the ambulance couldn't get there, or that a woman gave birth while waiting in line.

They had already run out of food when news reached them that families with children could cross the border on foot. They decided to abandon their car.

They walked for eight hours, from 8am to 4pm, carrying Victor in their arms. They would pass him from one to the other. Everywhere around them: dirt, the smell of urine and feces. They were exhausted, the little boy would lose patience from time to time and start crying. To make the journey easier, they invented all sorts of games. Like "Who gets to the house with the red roof first". Like "Guess what that interesting tree is?". And many other that even disconnected parents from their own thoughts.

When they got to the border, they could hear the customs officers yelling at the people: "Traitors!"

They just got in line with other families with children when they heard the roar of a powerful engine from behind. An armoured army car was swarming towards them... an ominous sight.

"A mobile military command post had been set up right near the border. They were checking us off a list. There were people who were already on the list, the soldiers didn't allow them to cross over and they were sent back."

High-risk rents

The large number of Russians crossing the border into Georgia and Armenia has caused rent rates to rise as much as fivefold. Decent places were getting harder to find. "Armenians and Georgians thought that rich people were crossing over, they knew that many IT people had fled. But they didn't think there were IT people who were out of work," says Maria.

Andrei, Maria and Victor have changed six homes in three months. They first found a place to rent that smelled strongly of paint thinner and had no heat. Then a kind-hearted woman took them in and set up a place for them to sleep on the kitchen floor. Then they found a room with another landlord, in fact a four-square-metre closet with no windows. They lived for two weeks in a hostel that smelled of gas. A few days after they left there, there was an explosion, people ended up in hospital. Finally, after three months of waiting, the visas came through and, with the last of their money and some loans, they bought a plane ticket to Cluj.

Romanian and Ukrainian roots

Ioan Pop was born and raised in Russia. His mother's father, Ioan's grandfather, was from Turda. He fell prisoner to the Russians in the First World War and was taken to a labour camp in the Urals. Seven years had passed when he met a young Ukrainian woman, a simple peasant girl who had been widowed with a young child as a result of the war. They married and had two children.

John's grandfather, Victor's great-great-grandfather, tried for his whole remaining years to return to Romania, to his family, but the authorities wouldn't allow him to leave. In the late 1930s, before the outbreak of World War II, he was declared an enemy of the people, arrested and executed.

Ninety years later, Ioan Pop made his dream come true: he returned to Romania and received citizenship. Now his son and grandson are returning, also driven by war.

Two winter jackets and another one, already too small, hang on the hallstand of Ioan Pop's small apartment. It's been a month since Victor hugged his grandfather for the first time, and now he's playing with cubes while his parents are taking Romanian lessons with Ioan.

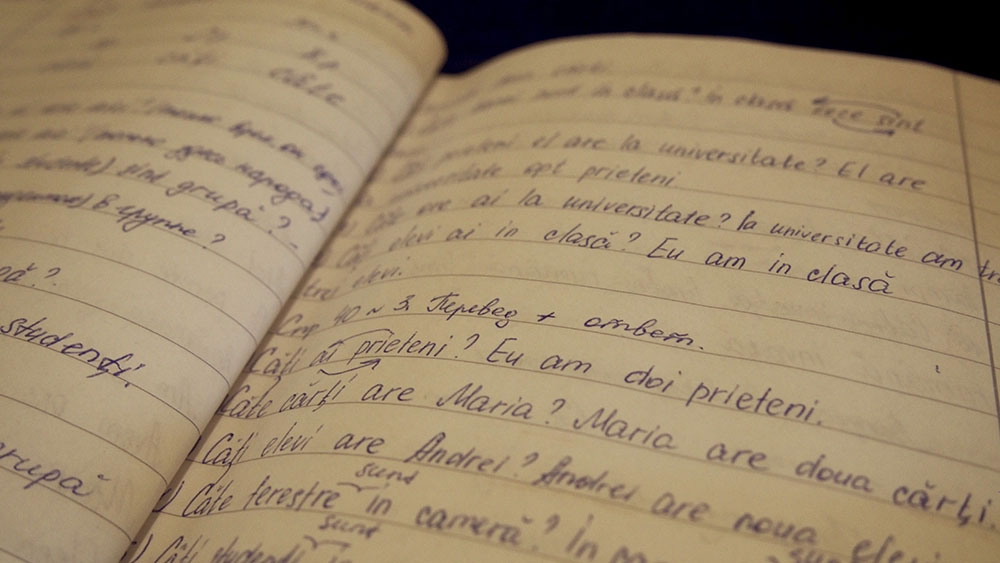

He teaches them Romanian from a xeroxed copy of a Russian-Romanian textbook. A 1982 edition. "Years ago I paid a full salary for this copy. Now I hardly found it... it's the one I learned from. You don't find many Romanian textbooks for Russians," he says.

From the same A4 pages he had also learned Romanian, in his 50s, when he decided to leave Russia, to move to Cluj and find his roots here.

Andrei and Maria have their notebooks open on the table. Maria has beautiful calligraphy, Andrei is not too proud of his. He says he's more used to the keyboard.

Next to them, Victor has just finished building a house out of cubes.

"Smotri, ya sdelal dom!" (Look, I made a house!)

"Dom means home," Ioan says in Romanian, gently tapping the house with a finger. "Cluj, home."

Note: To protect the people mentioned in this article we have changed the names and other details of their identity.

RELATED

Mobilisation at the borders

261,000 men fled Russia at the end of September, 2022, following the announcement of partial mobilisation, according to Reuters.

Russians arriving in Romania

30,000 Russian citizens have transited Romania since the war in Ukraine began, fewer than a year earlier. Of these, almost 500 decided to stay in our country. (Source: INS, via Pro TV)